Transit cuts dressed up as progress: Muni's faux “frequent” plan

September 27, 2021

In the dark days of April 2020, before Covid-19 vaccines existed, Muni made unprecedented service cuts so it could safely provide “essential trips only.” This drastic step was intended to be temporary, for emergency response only, and most lines have since returned. The exceptions: there’s still no 2-Clement, 3-Jackson, 6-Haight/Parnassus, 10-Townsend, 21-Hayes, or 47-Van Ness—nor any of the express routes.

Now Muni proposes not to restore most of these at all. A survey about Muni’s 2022 network provides a full restoration option, but condescendingly calls it the “familiar” alternative, as though it had no other positive qualities. While stressing that the decision is up to you and me, the survey’s text editorializes heavily in favor of two alternatives that reduce Muni’s coverage of the city, more or less dramatically. These are branded as “frequent” and “hybrid.”

The pitch behind the “frequent” plan is that it’s better to consolidate parallel bus routes that are close together. In theory, this makes sense. A single bus that comes every 5 minutes seems more useful than two buses that come every 10 minutes and run only a block apart.

When you look at what’s actually being proposed, though, it’s less convincing. The existing bus routes aren’t as duplicative as you might think—and the frequency benefits are much less dramatic than they seem. These “frequent” and “hybrid” proposals to reduce the Muni network are ill-timed at best, and at worst represent a major step backwards for transit, for several reasons:

-

The actual frequency gains are exaggerated, in some cases as minor as 5 versus 6 minute scheduled headways—which would disappear into the noise of actual bus performance.

-

Ignoring density, demographics, hills, and other factors, Muni dismisses service as redundant that’s actually vital. Major destinations would be separated from transit by unrealistically long or steep walks.

-

Sloppy, error-filled descriptions of pre-pandemic service show that Muni poorly understands the service it proposes to remove.

-

Proposed changes mostly remove service from retail corridors, schools, residential neighborhoods, and recreation, despite claims they’re needed to adapt to less downtown commuting.

-

Lack of clarity over whether network changes are permanent or not compromises the outreach being done and the quality of feedback Muni will get from riders. The uncertainty alone could make people give up Muni for cars, and be less likely to vote for transit funding.

-

To meet sustainable transportation goals, Muni must double transit ridership by 2030. A binary choice between frequency or coverage doesn’t make sense at such high levels of ridership. We’ll need both—high frequency and high coverage.

Before I go into these points, note that you can review the proposal here and submit feedback until this Friday, October 1st.

Frequency gains are exaggerated

If more frequent buses are the reason we’re making riders walk farther, you would hope the frequency wins were game-changing. Are they?

It’s immediately obvious from Muni’s proposal that some are not. For example, the 22-Fillmore would go from every 6 minutes to every 5 minutes, as would the combined 6 and 7 on Haight Street. Taken at face value, this is not something the average rider will notice unless buses are crush-crowded. And in practice, Muni doesn’t always run its buses precisely enough to realize such a difference. This tweak does, however, let the SFMTA market these routes as a “Five Minute Network” and draw misleading charts with an artificial boundary at 5 minutes.

Even more eyebrow-raising: Muni admits Van Ness service would decrease from every 4 minutes (47+49 combined) to every 5. Yes, you read that right. After years of construction on Van Ness, bus rapid transit would launch with less service than before—under the “frequent” plan.

There are some winners, notably the 5, 12, 30, and 45.

For 5-Fulton riders east of 8th Avenue, doubled service from every 10 to every 5 minutes is a genuine improvement. The SoMa and Financial District segment of the 12-Folsom would go from every 15 to every 7.5 minutes, a big win, if somewhat of a head-scratcher when the rationale for these changes is fewer downtown trips (more on that later).

On the crowded 30 and 45, a 33% service increase would be very welcome, although one wonders if transit-only lanes could achieve similar results without cutting elsewhere. These buses tend to get stuck in traffic jams on Columbus and Stockton, which are missing from the SFMTA’s transit lane plans. Note also that the Central Subway duplicates the busiest part of the 30 and 45 and is predicted to open in spring 2022.

Except for those four lines—the 5, 12, 30, and 45—no service increase in the “frequent” alternative cracks 25%. There are as many service decreases as there are substantial increases. I did the math, based on both the survey and the weekday frequency guide (archive), to paint a more complete picture:

| Route or segment | "Familiar" headway | "Frequent" headway | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1+2 Inner Richmond1 |

6min | 8min | -25% |

| 2+3 Japantown, Lower Nob Hill2 |

10min | Eliminated | -100% |

| 5 | 10min | 5min | 100% |

| 5R | 10min | 10min | 0% |

| 6 Ashbury Heights |

12min | Eliminated | -100% |

| 6 (or 52/66) Parnassus/GG Heights |

12min | 20min | -40% |

| 6+7 on Haight |

6min | 5min | 20% |

| 7 on Lincoln |

12min | 10min | 20% |

| 10+12 on Pacific |

8min | 7.5min | 7% |

| 12 SoMa |

15min | 7.5min | 100% |

| 12 Mission Dist.3 |

15min | 15min | 0% |

| 14+14R+49 Mission/Excelsior4 |

2.7min | 2.2min | 23% |

| 215 | 12min | Eliminated | -100% |

| 22 | 6min | 5min | 20% |

| 286 | 12min | 12min | 0% |

| 30 on Columbus |

8min | 6min | 33% |

| 30+45 on Stockton |

4min | 3min | 33% |

| 43 to Fort Mason |

12min | Eliminated | -100% |

| 47/28 on North Point |

8min | 12min | -33% |

| 47+49 on Van Ness |

4min | 5min | -25% |

Due to time limitations, I didn’t analyze the “hybrid” alternative quite so systematically. The general pattern is that in “hybrid,” the actual service increases in “frequent” are diminished or lost, while some routes are restored at a minimal 20 minute headway instead of being cut. On Van Ness, BRT manages to fare even worse under “hybrid,” launching with a third less service than Van Ness had pre-Covid.

Not all parallel lines are redundant

We’ve seen how the benefits of the “frequent” and “hybrid” alternatives are lacking. What about the costs? If the service being removed is redundant, maybe it’s no big loss.

A case for consolidation: the 2 on Clement

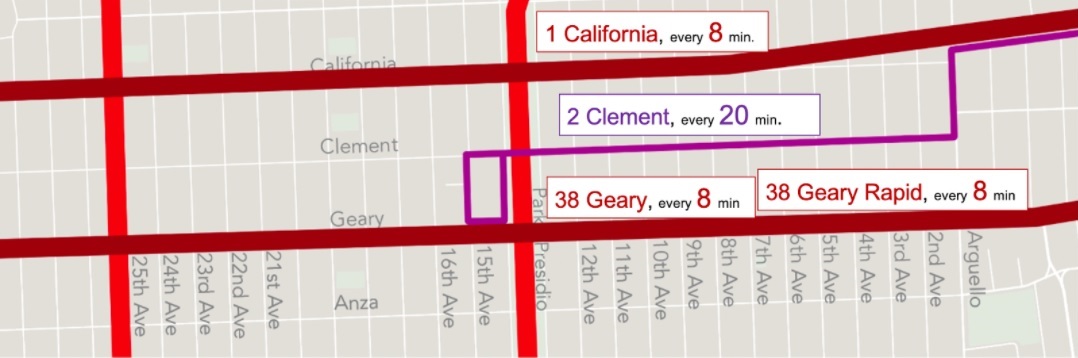

This reasoning is on its firmest ground when discussing potential elimination of the 2-Clement in the Inner Richmond, where its route parallels the 1 and 38 a block away. Not coincidentally, a blog post by Jarrett Walker, the consultant SFMTA hired to oversee this redesign, trots out exactly this segment to justify route consolidation. Walker includes the following image:

I want to emphasize that this segment of the 2 is the best possible case for route consolidation. It’s uniquely only one block from parallel transit, while every other segment removed under “frequent” adds a 2-block walk at least. And the Inner Richmond is flat. If there’s a segment that should be removed, it’s this one.

Even so, I want to make a little bit of a case for the 2-Clement. The thing is, Clement Street here is a dense, hopping retail and restaurant corridor, the Main Street of the Inner Richmond. On California and Geary, retail exists but is patchier. For example, Geary from 9th to 10th Aves has only a mortuary and Shell gas station. Clement from 9th to 10th Aves features five restaurants, a brewpub, a post office, a bookstore, a seafood store, a produce store, a music education center, a travel agency, a bank branch, and a beauty salon. And that’s one of the quieter blocks of Clement.

It’s hopefully obvious that when people see bus stops while on a shopping trip that they might have driven to, they’re more likely to try the bus next time, as opposed to “out of sight, out of mind.” Conversely, a steady stream of bus riders passing through might be a lifeline for small business owners struggling after pandemic losses. You can cite Valencia Street across town as a success with the transit a block away on Mission, but in that case Mission Street is an equally strong retail corridor (if one that caters to less affluent customers).

Even if none of these factors ultimately justify the duplication, you would hope they’d be considered. Yet in a 1,000-word blog post, none of this is mentioned. It’s all math and adding up walking times and wait times, ignoring the reasons why a bus runs here in the first place—and what people are in the neighborhood to do. The SFMTA’s consultant, who titled his book and blog “Human Transit,” has removed the humans from his discussion of transit.

What hills? The 6 and 21

Hills are a fact of life in San Francisco. Muni rightly factors them in when deciding how far apart bus stops should be. So why not when deciding how far apart bus routes should be?

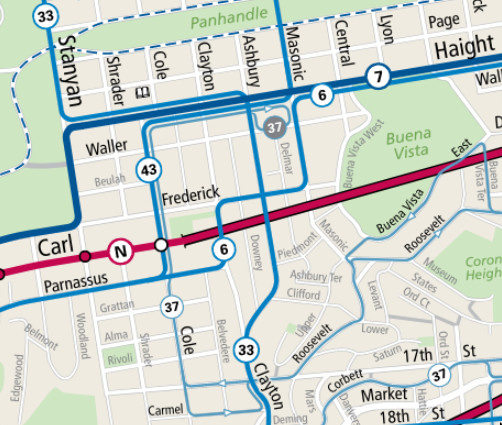

Consider the 6. Coming east from UCSF’s Parnassus campus, the 6-Haight/Parnassus follows the ridgeline east to Clayton, north one block to Frederick, and east two blocks to Masonic before dropping down onto Haight St and joining the 7. This route isn’t random. At any point on the Clayton-Frederick stretch, if you look down in the direction of other buses, you’re going to see at least a 10% grade—Muni’s threshold for putting bus stops closer together.

You’ll also look up and see 10-15% grades: for many residents of Ashbury Heights and Buena Vista Heights, losing the 6 has doubled not just the walk to access Haight St retail, but the elevation gain as well. Both the “frequent” and “hybrid” alternatives would make that loss permanent. Per the survey, “Ashbury Heights…is also served by the 33 Stanyan,” but the 33 isn’t a parallel route, it’s a perpendicular one, serving entirely different destinations.7

Moving east, the 21-Hayes is on the chopping block in favor of the 5-Fulton and 7-Haight/Noriega. These are three and four blocks away, respectively, which already puts Hayes more than a quarter-mile away from transit, depending on the cross street. Now add steep hills. The Painted Ladies used to have their own stop; now, when your out-of-town parents want to come see them, they’ll have to hoof it up a 14% grade from the 5. Students at Ida B Wells High have a four-block walk from the 7 which averages a 9% rise.

I mentioned before that on Clement, the 2 is at least flat. Not true elsewhere. Further east, where the 2 and 3 would both be eliminated under the “frequent” alternative (or have service cut in half under “hybrid”), the walk to transit becomes as long as four blocks8, on some of the steepest streets in the city that can top 20% grade. Cutting these routes tells people who live in or visit these areas, “Give up and drive.”

Fort Mason: for drivers only

In September 2020, Jeffrey Tumlin tweeted he was thinking of renting a car to go to a drive-in movie at the Fort Mason Center that strictly banned non-drivers.9 A year later, the bus still doesn’t go there, and Tumlin’s agency is proposing to leave it that way. Visitors to this major cultural destination and its bar, restaurant, museum, educational and other tenants would have to walk 3 blocks from the 22, 4 blocks from the 30, or 5 blocks from the 28.

As the survey explains, keeping the shortened 43 “would mean no direct Muni service to the front door of Fort Mason or the adjacent Marina Safeway, although those would still be within a quarter mile walk” of the 22 and 30. Is lugging your Safeway bags a quarter mile what efficient transit looks like?

In the end, the 43 to Fort Mason Center will probably be restored. At a September 21 board meeting, asked about numerous comments against this service cut, an SFMTA manager of transit planning sheepishly acknowledged the “helpful feedback.” But it’s appalling it was even considered.

Misstating pre-pandemic service

So the team working on this redesign missed quite a few topographic and human factors. If you think you can do better than the “routes that have been part of San Francisco for years” (SFMTA’s words), shouldn’t there be more attention to detail?

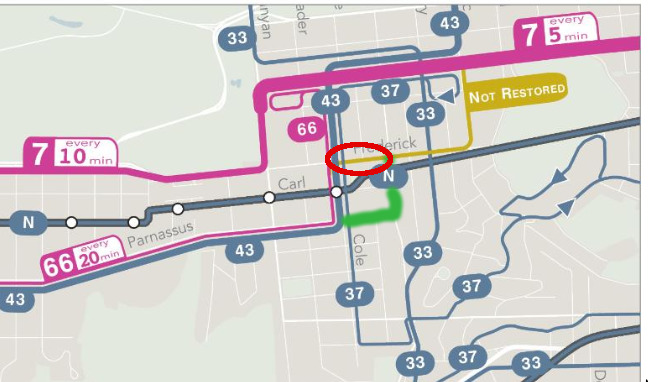

Unfortunately, that’s not all. Presentations and blog posts about the redesign have repeatedly misstated what pre-pandemic service was. For instance, maps of the 6 route under the “frequent” and “hybrid” options don’t show that service is being removed along Clayton St. They instead falsely suggest the 6 used to run a block over on Cole, duplicating the 43 for that block.

For three weeks, the error has gone unfixed in the maps attached to the survey, and it was also present in a slide shown to SFMTA board members at the September 21 hearing, and again in a slide shown to supervisors (in their role as Transportation Authority commissioners) in today’s TA meeting. This hides the full extent of transit access being sacrificed in Ashbury Heights.

The survey also suggests that under the “familiar” alternative, the 21-Hayes would be “Restored as it was, every 12 minutes” (an earlier revision said every 15 minutes). But the scheduled 21 headway before the pandemic was not 12 or 15 minutes, it was 7 in the morning and 10 midday.

Is the redesign based on midday frequencies? 10 still isn’t 12. And if that difference seems insignificant, remember that the redesign highlights 5 versus 6 minute headways as a win for the “Five Minute Network.”

Changes hurt non-commute trips

After all the talk of how San Franciscans are making fewer downtown trips, which is supposed to be a motivating factor, the “frequent” plan’s changes don’t line up.

To tie together a few examples already mentioned: the burden of route cuts falls hard on residential neighborhoods (Ashbury/Buena Vista Heights), retail and nightlife (Clement), recreation (Alamo Square Park), arts (Fort Mason), and education (Ida B Wells High).

The biggest frequency gains would be on the segment of the 12-Folsom that serves SoMa and the Financial District and on the 5-Fulton, including its long stretch on Market into downtown (but excluding the Central and Outer Richmond segments). Don’t get me wrong: I’m not against increased service downtown. People will return to offices eventually, and Muni should be there for them. But I agree with the SFMTA’s assertion that neighborhood service should probably be the priority right now, which makes it odd how little the “frequent” alternative actually realizes that.

One major change shifting resources away from downtown is the removal of all express lines (14X, 7X, NX, 8AX, etc.), but this is the case in all three alternatives. And even then, an exception should be considered for the 76X Marin Headlands Express, which provided weekend and holiday service to trails and beaches. It’s an express, but not a commuter line, and based on the pattern of surging Saturday ridership BART is seeing, it would probably be well-used if restored now.

If it’s cut, will it come back?

So the frequency gains in the “frequent” alternative are overhyped, they don’t actually shift resources away from downtown, and they come with a severe loss of access. But at least this is temporary, right? It’s just the winter 2022 service plan. Couldn’t the 2, 3, 6, 21 and 47 be left unrestored for now, and still come bouncing right back when funding is approved?

It’s unlikely. Look at how the changes are being talked about. Start with that July 15 blog post. It asks rhetorically: “When a transit agency comes back from the COVID-19 crisis, should it aim to put back service the way it was, or try to put back something better?” Even before the pandemic, “ongoing trends… have shifted travel patterns away from a single focus on downtown… So are we sure we want the network to be exactly as it was?” That’s a clear call for permanent changes.

A week later, on July 23, there was some backpedaling when SFMTA head Tumlin, accused by supervisors of de facto abandoning routes, denied it: “There’s no plan to eliminate these lines.” But Tumlin also said he was “asking basic and fundamental questions about the future of Muni,” which would seem to include the possibility of eliminating lines. He added the changes would last an additional two years.

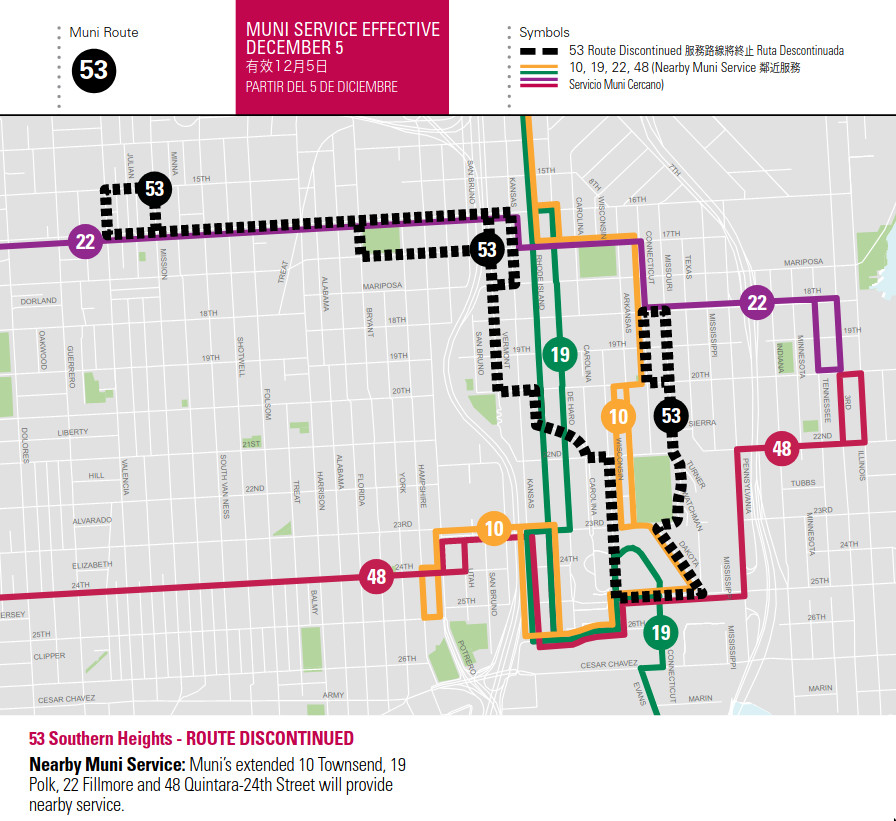

With mixed messages coming from the SFMTA, we can look to history. Route cuts tend to be sticky—much more so than small headway tweaks. Ten years after a deficit forced Muni to reduce service in 2009, we still hadn’t seen the return of the 53-Southern Heights, the 26-Valencia, or the 2-Clement’s Outer Richmond service.

The 2030 city: Doubling transit ridership

For several years now, the SFMTA has set the goal of 80% of trips in San Francisco being made by sustainable modes by 2030. In July, the Board of Supervisors embraced this goal, unanimously passing the 0-80-100 Roots climate framework, where the “80” refers to 80% of trips in San Francisco by low-carbon modes: transit, walking, and bicycling, not cars.

This goal is ambitious, to put it mildly. Last time San Francisco measured this in 2019, only 47% of trips were sustainable (or low-carbon), and that was down from 2017.10

Let’s suppose transit, walking and bicycling trips grow at the same rate, that these trips replace car trips, and that San Francisco’s population grows equally as fast during the 20s as it did during the teens.11 Then to meet the goal, transit rides will have to increase to 185% of their 2019 level.

Round it up: Muni needs to double ridership.

Now look back at the tradeoffs we’re asked to accept. Frequency or coverage, not both. Residential neighborhoods, commercial corridors, and parks farther away from the bus. Is that what doubling transit ridership looks like?

In a vision that takes this goal seriously, choosing between high frequency and wide coverage is nonsensical. We need both. There are going to be plenty of riders on both the 21 and the 5, both the 38 and the 2, both Haight St (served by the 7) and Parnassus, Clayton and Frederick streets (served by the 6).

Conclusion: Funding the transit we want

The main barrier to 100%, let alone 200%, of pre-pandemic transit is funding. The SFMTA’s own revenue from fares, parking fees and fines, plus contributions from the City’s general fund, doesn’t add up to enough to pay expenses. One-time relief funds have hit “snooze” on this problem, not solved it. For now, Muni’s settled on only providing 85% of pre-pandemic service because that’s what they can sustain, without:

- a local 2022 ballot measure for dedicated funding,

- a greater general fund allocation from the mayor and Board of Supervisors, and/or

- federal transit operations funding (Senator Ossoff’s bill).

Your supervisor has a huge impact on the viability of those first two options, so when you talk to them, it’s important to not only criticize Muni’s plans, but ask for a general fund increase and support for a transit funding ballot measure. $85 million, the estimated cost difference between delivering 85% and 100% of pre-pandemic service, is only 0.7% of the City budget.

Unfortunately, Muni—or specifically Tumlin and the consulting team; I’m sure not all staff support this—has muddied the waters. Instead of just coping with a bad budget crunch and admitting that, they’ve framed their changes as providing better, more frequent service. It’s a mostly false pitch that disguises a reality of making transit less convenient and more difficult for many San Franciscans to use.

The result is that transit advocates have to wage a two-front war against both the political apathy that lets transit go without proper funding and a narrow technocratic vision that disregards the accumulated wisdom of the Muni network to hastily justify cuts.

It would be much better if advocates could fight hand-in-hand with Muni for the resources Muni needs to operate great service, with high frequency, high coverage, and high ridership. We can get there if Tumlin and the SFMTA board abandon the route cuts in this faux “frequent” alternative and opt for the fullest route restoration possible.

Links / more reading

- Fill out the survey open until October 1st

- SF Transit Riders response to 2022 plans

- Chris Arvin’s 2022 Muni trip comparison tool

-

The west end of the 2 was used as an example of redundancy in consultant Jarrett Walker’s blog post, but the “frequent” plan removes it without boosting parallel lines. Here I analyze average headways of the 1 and 2 combined, which pre-Covid (and under the “familiar” alternative) run together on California from Presidio to Arguello, and a block apart from Arguello to 14th Ave. Even if you disregard the benefits of having transit right in front of shops and restaurants versus a block away, “frequent” is a pure loss for this corridor. ↩

-

No corresponding service increase on 1 (3-4 blocks north) or 38/38R (2 blocks south). ↩

-

South of 16th St. ↩

-

Averages combined frequency of the 14 every 7min, 14R every 10min, and either 49 in “familiar” every 8min, or 49R in “frequent” every 5min. ↩

-

See 5 (2-3 blocks north) and 6+7 on Haight (4 blocks south) for parallel service. ↩

-

In “frequent,” the 28 takes a more circuitous route that avoids the Palace of Fine Arts and is purportedly a replacement for Fort Mason service (even though that requires a 5-block walk), so I included it despite the unchanged frequency. ↩

-

In 2014, a similar but more generous proposal would have taken the 6 off this segment but rerouted the 37 and 43 onto it to make up for the loss. ↩

-

In this part of the city, streets are one-way, so the length of walk to the bus depends on which direction you’re going. Traveling east to a destination on Bush St required a two-block walk before (from the 2/3 on Post) and now requires a four-block walk (from the 1 on Clay or the 38 on O’Farrell). The block from Jones from Pine to California has a 24% grade. ↩

-

For comparison, Berlin has just set a goal of 82% sustainable trips by 2030, and they have much less distance to cover, as they are already at 74% today. ↩

-

That may be an underestimate, since the state will ask San Francisco to build significantly more new housing between 2023 and 2031. ↩