The myth of “transit streets, bike streets and car streets”

April 26, 2023

At a February workshop called “Building Trust With Our Communities,” San Francisco’s MTA board reflected on the importance of trust and how to earn it. What the board came up with isn’t clear, but it didn’t stop them from, two months later, unanimously approving center-running bike lanes on Valencia, a design that increased crashes in Washington, DC1 and which only 13% of respondents supported.

Valencia Street is often described as one of a triplet of parallel streets segregated by mode. Where Valencia is the “bike street,” Mission, with bus-only red lanes for the 14 and 49, is the “transit street,” and Guerrero (or South Van Ness) is the “car street.” In 2018, Streetsblog San Francisco reports that an SFMTA planner explicitly cited this as the City’s philosophy: “Mission should be the transit-priority street, Guerrero Street should be for cars, and Valencia is the bike street, the people street.” A similar formulation is sometimes heard in the Haight-Ashbury, where Haight is the transit street, Page the bike street, and the one-way couplet of Oak and Fell are the car streets. A third potential example of this philosophy is seen between Civic Center/Hayes Valley and Fort Mason, with Polk as the bike street, Van Ness the transit street, and the Franklin/Gough couplet the car streets.

If you squint, you can sort of see this pattern on the west side: In the Richmond, Geary is the transit street, California the car street, and Lake the bike street (but you have to skip Clement). In the Sunset, Kirkham is the bike street, Judah the transit street, and Lincoln the car street (jumping over Irving).

The problem with this formulation? All of these are actually car streets.

Every one of these so-called bike streets and transit streets lets cars park on both sides for most of its length. They all allow cars to through-travel for a mile or more in at least one direction, if not the entire length of the street.2 With the possible exception of Page, none meet NACTO low-stress criteria of fewer than 1,000 vehicles per day at speeds under 15 mph.3

And none of this was even up for debate on Valencia, “the bike street, the people street.” Instead, staff, acting under dictates from Mayor London Breed, forced board members and advocates to reluctantly back the questionably safe, unpopular center bike lane design as the only available option.

“I wish we had more options here, but we have what we have,” said SFMTA board director Steve Heminger. “The pilot is the only option on the table,” San Francisco Bicycle Coalition director Janelle Wong concurred.4 “Is this my first choice? Absolutely not, [but I’m] desperate for improvements,” said Valencia resident and former SF Bike Coalition board member Amandeep Jawa. SF Bike’s Nesrine Mazjoub said, “While we do have hesitations… we aren’t being given any other option.”5 “Many of us aren’t in love with a center-running bike lane, but something needs to be done,” summarized Supervisor Hillary Ronen, who represents the street.6

Those are the endorsements of people who supported the plan.

Officially, side-running protected bike lanes were ruled out because they interfere with outdoor dining (in the form of parklets). But there are other options that don’t. Valencia could become a full or partial car-free promenade, as piloted on Fridays and Saturdays from 2020 to 2022. Cars could be restricted to one-block, local access only via concrete barricades, which the City didn’t hesitate to quickly install on Capp in response to nuisance complaints about sex work. Or Valencia could be made one-way for cars, freeing space for a truly protected bikeway, commercial loading, and more al fresco dining. Any of these options or a mix of them could create a truly safe, welcoming “bike street, people street” we’d fall in love with.

Center-running bike lanes weren’t the only option. They were the only option that kept Valencia a car street. For the mayor, that was the point.

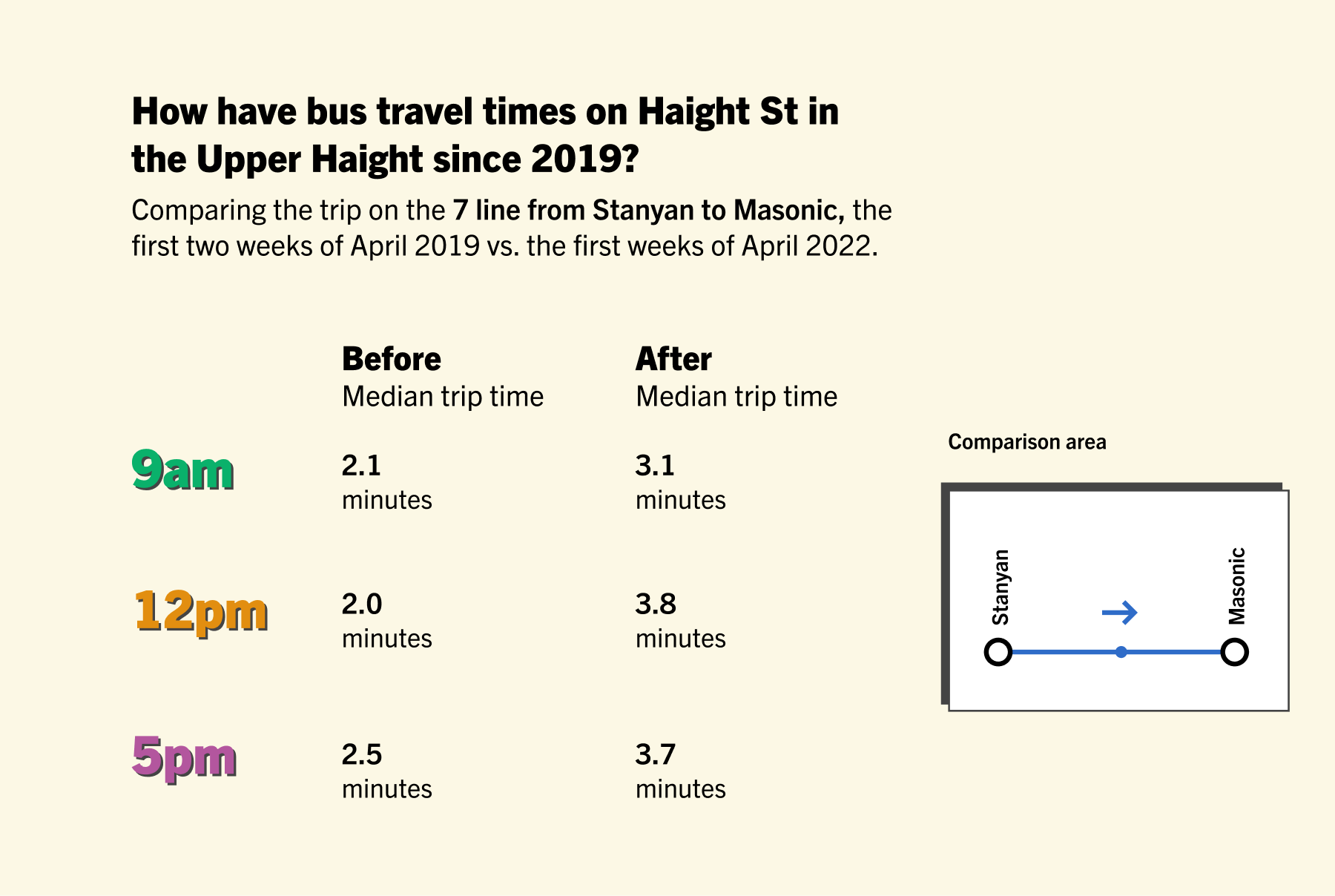

Meanwhile on Haight Street, a supposed “transit street,” traffic signals that replaced stop signs in 2021 were pitched as a way to speed up the 7 bus. They didn’t. But they do allow cars to move faster through intersections, putting pedestrians and bikes at greater risk in a collision, exactly as residents feared when the signals were first proposed in 2015. What would a real “transit street” look like? It might have bus gates, allowing Muni buses but not cars to pass through key intersections, so that the signals don’t end up encouraging private car through-travel.

To be fair, SFMTA did remove access onto the Central Freeway from both Haight and Page streets in early 2020 as part of the Page bikeway improvements. It was a welcome start, an example of what taking “transit streets” and “bike streets” seriously might look like.

And while I call Van Ness a “car street” since it has curb parking and four car lanes its entire length—instead of, say, a bike lane, which would be handy at the north end where it’s flatter than Polk—it’s also true that Van Ness BRT has been wildly successful. Maybe Van Ness qualifies as a transit plus car street.

But examples like these are the exception, not the rule. Reflecting on 11 years on the SFMTA board, Cheryl Brinkman called Polk Street “the most missed opportunity… It still makes me angry and sad. We still don’t have that cross-city bike connection. Polk Street is still just not a good bike street.” As Brinkman said that, the City was actively resisting making what turned out to be bare-minimum safety improvements, even after a death.

“Transit streets, bike streets, and car streets” are a fiction. From Valencia to Polk, to Haight, to watered-down Slow Lake, they’re all car streets.

And if we took the Transit First policy at face value, they’d all be bike streets and transit streets. None of them would be car streets, at least not to the extent of Guerrero, Franklin, or Oak. But that’s a whole nother essay.

-

According to a report co-authored by Jamie Parks, who now directs the SFMTA department that designed the Valencia plan and was tasked with defending it to an SF audience. ↩

-

From 2020 to 2022, Page and Lake were Slow Streets that didn’t allow through traffic, but while they are still nominally Slow Streets, SFMTA has removed the “local traffic only” signs, and Jeffrey Tumlin told drivers the rule no longer applies. Page’s diverters are great, but none affect the westbound direction from Octavia to Stanyan. Mission Street has forced right turns for non-Muni vehicles, but even if those were actually obeyed, they only apply to northbound traffic. ↩

-

This is the official goal for the Slow Streets program, which Lake is technically still part of. Lake and Page met both criteria in the summer 2021 evaluation, but Lake only barely met the speed criterion, and both streets have seen increased traffic volume and speed after implementations were watered down. I’m confident enough to assert now that Lake fails the speed goal; a forthcoming evaluation will reveal just how badly it misses it. Update, April 28, 2023: Data gathered by a Slow Lake supporter via a Telraam camera shows that the 85th percentile speed is actually below 15 mph most times of day, but that the volume of cars greatly exceeds the 1,000 threshold: it was 1,617 cars on April 26th. ↩

-

Quoted in Lingzi Chen, Valencia center bike lane pilot approved, Mission Local, April 4, 2023. ↩

-

Quoted in Eleni Balakrishnan, Valencia center bikeway likely to pass, despite weak support, Mission Local, March 30, 2023. ↩

-

Quoted in Garrett Leahy, Controversial bike lane in middle of SF’s Valencia Street approved by transit bosses, SF Standard, April 4, 2023. ↩